Xi Jinping would make Deng Xiaoping roll in his grave

As Machiavelli once said, “no enterprise is more likely to succeed than one concealed from the enemy until it is ripe for execution.”

It was something Deng Xiaoping, the man who built modern China, understood. It is something China’s current leader does not understand at all.

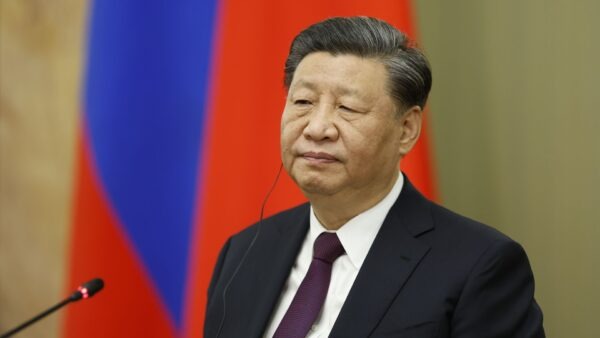

Current Chinese president Xi Jinping has excelled in putting his needs above that of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), which has ruled China since 1949, and scuttling carefully prepared plans to ease China into a position of international supremacy. These plans were put in motion decades prior to Xi’s ascent to leadership by Deng himself.

Deng was an exceptionally intelligent man who planned in generational terms. Indeed, his and Xi’s goals for China are more or less aligned: the reclamation of Taiwan, the assimilation of Hong Kong, dominance in the South China Sea and Chinese supremacy over the United States.

One of the many differences between Deng and Xi is that Deng knew China had to bide its time and play nice with the world while it grew in strength. His charm offensive, beginning with his visit to America in 1979, was part of that strategy.

Such preparation, especially when competing with a behemoth like America, takes decades. Deng understood, like Machiavelli, the importance of patience. He knew that the seeds he planted would not bear fruit until long after he was gone.

This is not to call Deng a saint. After all, he was a part of a system that has oppressed the Chinese people since the Mao era. It was under Deng’s leadership that one-party rule continued after Mao’s death. It was Deng who denied the Chinese people a democracy as calls for freedom grew louder. And it was Deng who pushed for the bloody crackdown at Tiananmen Square in 1989 when those calls reached their apex.

But we’re speaking of selflessness and patriotism in CCP terms. Deng equated the achievement of the party’s goals with the success of China itself and he put the party ahead of his own personal ambitions.

Xi’s impatience, meanwhile, is palpable. It is not enough for him to push China further toward to final goal; he must be the one to cross the finish line. Thus, Xi has revealed the CCP’s hand far earlier than the long-term strategy demanded.

In place of a charm-offensive on the world stage is “wolf warrior diplomacy” – needlessly aggressive diplomats that alienate those that would facilitate China’s continued rise. There is also the blatant aggression along its ocean borders with Vietnam and the Philippines that prompt a response from the American navy. And the crackdown in Hong Kong that dispels any illusion that China would transition to a democracy; thus snapping the West out of their false sense of security.

Then there is the expected invasion of Taiwan within the next decade. Such an invasion, with China’s current military and naval capabilities, would be so precarious and costly a quagmire that Putin’s invasion of Ukraine would seem like a day at the seaside in comparison.

Much of the world, who had so willingly fused their economic needs with Chinese trade to the point of dependency, is thinking twice before relying on China further. A growing consensus is forming across western democracies that China is a threat.

But it is not just the CCP’s long-term goals that Xi threatens with his selfish hunger for immortality; it is the CCP itself.

Many in China grinned widely when Donald Trump, a kleptocratic authoritarian, became U.S. president. For China’s ruling class; it was a demonstration of “American-style” democracy’s fragility and artifice.

What that ruling class failed to see, however, was that their system of governance was just as fragile. Where Trump is a potent risk to popular American franchise, Xi was that same risk to the franchise of the CCP. The only difference between the two is that Trump’s ultimate success is still uncertain.

It is shocking how easily his party allowed Xi to execute his silent coup. Indeed, under the guise of an ‘anti-corruption’ campaign, Xi purged the party leadership of those not loyal to him and consolidated his control.

Deng would recoil at such blatant prioritisation of personal interest. After Mao’s chaotic and quasi-imperial reign, Deng excised Mao’s cronyism and cult of personality from the party like tumours. He brought back those exiled by Mao – men who challenged Mao on his atrocious policies – and filled important government positions with competence as the primary consideration.

Deng also established the concept of “collective rule” - the military, the government and, most importantly, the party should not, cannot, be consolidated around one man ever again.

Xi has changed everything. The Politburo Standing Committee is comprised of his cronies. The military is under his control. Loyalty to the leader trumps all other factors. “Collective rule” no longer exists. The Mao era returns.

But Xi inherited something that Mao had not: a flourishing economy. However, such a transformation of China’s fortunes did not happen by chance. They happened precisely by rejecting the self-obsessed political games that Xi has now fully embraced.

It may be too late for Xi to undo the damage he has wrought. We’ll see if the economic engine that he inherited is enough to save his homeland from its greatest threat: himself.

Post a comment